A Critique of Stoicism

Before we begin our critique of stoicism, it is important to understand what stoicism is, and what it is not.

Stoicism was founded by the Greek philosopher Zeno (pictured left) in the 3rd century BC. The Stoics were one of the few philosophical movements that met in public, gathering on the poikílē stoá, or painted porch, of the Agora in Athens. It was from this location that they derived their name, making them literally “the porch people”. The modern usage of stoic as a “person who represses feelings or endures patiently” wasn’t used until 1579. Stoic ethics are completely deterministic. Under determinism, all new events are just the result of preceding events. The classic stoic parable is that of the dog tied to a cart. A wicked dog barks, pulls at the rope, and futilely fights as the cart makes its way down the road. A stoic dog instead happily follows the cart, even if the cart ultimately injures or kills the dog.

Prior to becoming involved in the Mazamas, I had a fairly stoic outlook on life. This mental conditioning began when I became involved in wrestling in middle school. You never wanted to show your opponent how tired or sore you were. My stoic predilections were accelerated when I became an officer. You never wanted your men to see your uncertainty, frustration, or disquiet.

For most of my life stoicism served me well. It allowed me to shed negativity and be a positive influence on those around me. That changed during my mountaineering team’s attempt on Middle Sister. I was the first to reach the planned location for our base camp, at 9,300 feet. I started work carving a shelf out of the glacier for our tent in high spirits. I then went on to boil and filter water for the team. It was about this time that I developed a headache and severe nausea. I was torn between either stoically soldiering on or disclosing my symptoms to the climb leader. When one of the other climbers went down with AMS (Acute Mountain Sickness) I knew I couldn’t keep it to myself anymore. I was advised to try to eat something, which I did and then promptly vomited up. Our team ultimately ended up retreating from the approach.

I felt terrible. A few days later I received the following feedback from my instructors: “You were feeling like crap on Middle Sister— but still helped make water for the team. We noticed this behavior— thanks for helping out, but also remember to take care of yourself— you can’t help others if you are personally compromised. You’ve got to be communicative about how you’re feeling … stoicism doesn’t count for much in the high alpine.”

Wim Hof, another stoic, made a much more ambitious mountaineering attempt, seeking to summit Mount Everest. For those unfamiliar, Wim Hof is famous for his extreme ability to control his metabolism and for his stoicism in cold environments. Unfortunately, his attempt also ended in failure. When asked about his retreat, he had this to say:

“So I had a deep mental conversation with my foot, and it reported frostbite. I appreciated it was the right thing to turn back; extreme cold is a teacher. The lessons come to you through the body. You just listen."

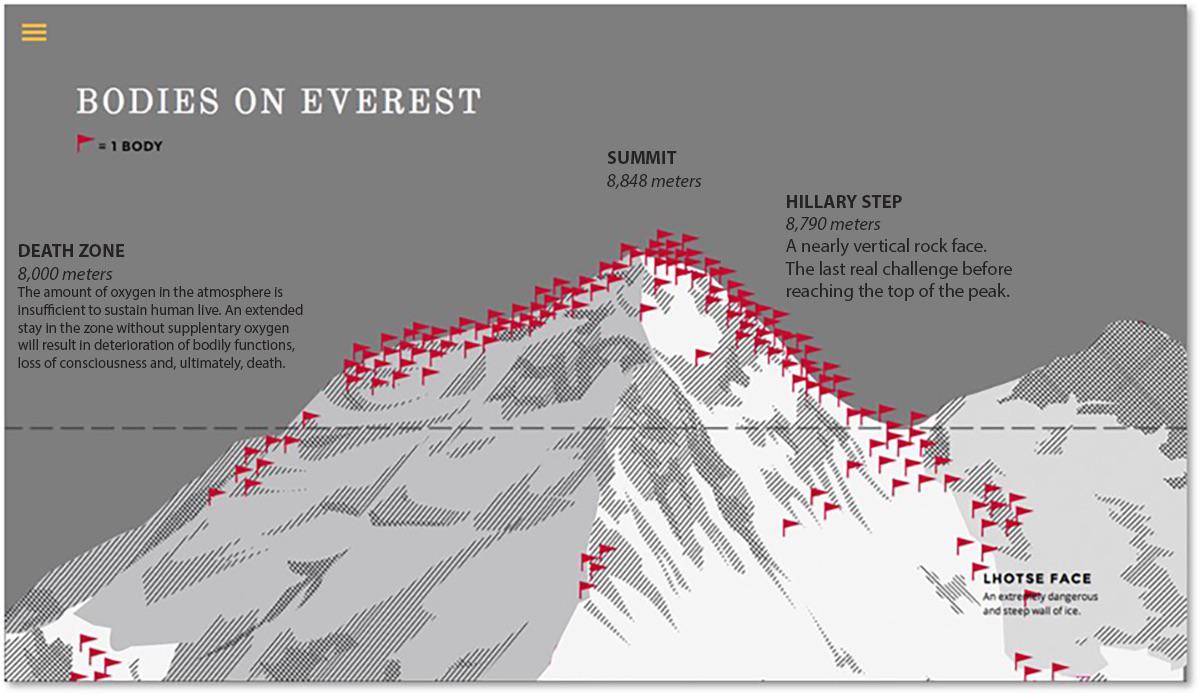

There are hundreds that didn’t listen. The chart below depicts all the unrecovered bodies on Mount Everest. Every one of those flags was at some point an extremely motivated person. They stoically persevered into the “Death Zone”. At that elevation the level of oxygen is insufficient to support human life. An extended stay will eventually result in loss of consciousness and death. They embraced their “destiny” and ultimately perished as a result.

Now that I’ve probably depressed 95% of you, let me bring it back a little bit. I’m not saying stoicism is worthless. Stoicism can be a very powerful tool to uplift those around you when circumstances appear their darkest, and to motivate yourself when all else fails. My critique of stoicism concerns its determinism. We aren’t dogs tied to carts. We can choose our circumstances, and adapt to them so that we survive to try again another day.

I’m also not saying that you shouldn’t try difficult things because you might fail. To quote Teddy Roosevelt:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat”

The important thing is to know your limits. You can (and should) push them, but never beyond the point of no return. Until next time.

Photo by Paolo Monti, 1969

comments powered by Disqus