Death and Taxes

It’s tax season again, and in the words of Benjamin Franklin “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” That’s why I figured this month I’d cover some tax “gotchas” that have snared me in previous years. I’ll specifically be addressing Roth Individual Retirement Account (IRA) contribution limits as well as Employee Stock Purchase Program (ESPP) and Restricted Stock Unit (RSU) sale tax implications.

Before I get too deep in the weeds I want to qualify that I am strictly a tax preparation amateur, parroting back what I learned during several tax seminars that my company was kind enough to sponsor. To quote Morgan Stanley’s own legal disclaimer, I cannot “provide tax, legal or accounting advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, tax, legal or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction.”

One of the first shocks that I encountered this year is that if your Modified Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) is above $228,000 for the year of 2023 you cannot make any contributions to your Roth IRA that year. Roth IRA contributions are important because all the money invested within a Roth IRA grows tax-free, enabling compound interest without the fetters of a capital gains tax. Your AGI is a rollup of all your earnings for the year, including wages, bonuses, dividends, investments, and gifts. It is calculated BEFORE deductions, so you can’t count on your child tax credit or charitable donations to bring you below the threshold. If you do exceed the threshold you can still contribute to your Roth IRA, but you have to do it in a somewhat convoluted way in what’s known as a “Backdoor Roth”. I don’t want to get too off track here, so I’ll simply link to this excellent investopia article.

The second surprise I found was that if you’re not careful you can end up being double taxed for ESPP sales. For those unfamiliar with ESPPs, they allow you to use up to 10% of your salary to purchase shares in your employer’s company, usually at a 10 to 15% discount. Even though I generally shy away from buying individual stocks because of their volatility, this is a pretty good deal considering the S&P 500 only averages 10% growth per year. That means that an ESPP can be a better bet than a broad-based index fund even if you’re in a company with a flat stock price.

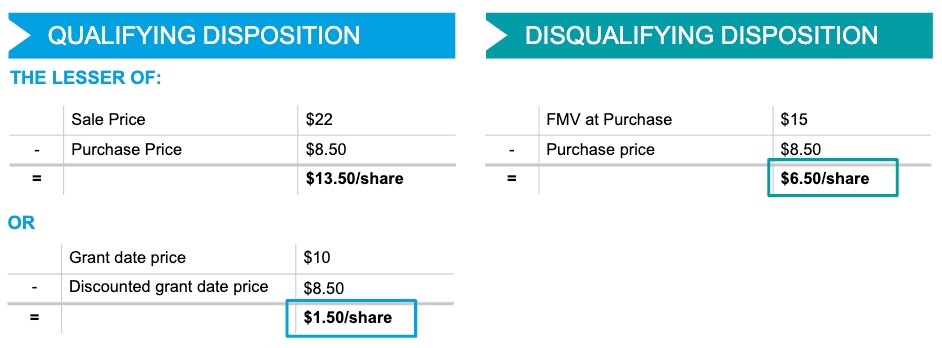

You can sell ESPP shares in one of two ways:

- As a Qualifying Disposition. In order qualify you must hold shares for at least two years after the grant date (the start of the ESPP offering period) and at least one year after purchase date. If your sale is a qualifying disposition you get to choose one of two formulas for your tax obligation:

- Taxable income = Sale price - Purchase price

- Taxable income = Grant date price - Discounted grant date price

- As a Disqualifying Disposition. If your sale is a disqualifying disposition you are locked in to the formula below:

- Taxable income = Full Market Value (FMV) at purchase - Purchase price

An example of a qualifying vs disqualifying adjustment is below:

When filing your taxes you should include the Supplementary Information documents from your ESPP’s website and manually calculate your tax obligation using a Form 8949 rather than taking the values reported in the ESPP’s 1099-B for granted. This is because the 1099-B will not have the adjusted cost basis, discounted grant price, or grant date price from the example above, potentially significantly increasing your tax obligation.

The final surprise that I found was that RSU’s have a similar, but thankfully simpler, “gotcha.” For those that haven’t received RSUs before, they’re stocks in the company that your employer gives you completely free of charge. The catch is you can’t sell them until after they’ve vested (the “Restricted” part of RSU), usually a year or two after they were initially granted.

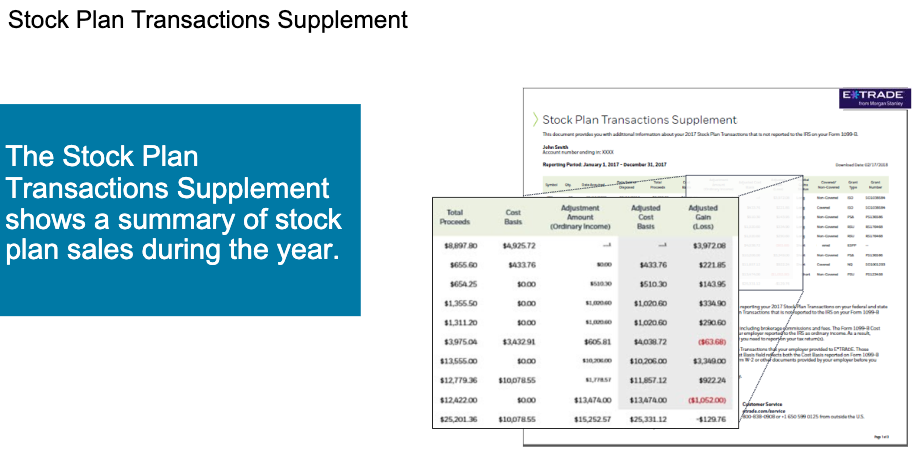

When you do sell RSUs your company reports the sale as income on your W-2. Unfortunately the sale is also reported as income by your company’s brokerage on, you guessed it, your stock plan’s 1099-B. This means that if your not careful you can end up paying twice. To resolve the issue you can check your brokerage’s website for a “Stock Plan Transactions Supplement” under tax documents section in order to get your adjusted cost basis. An example is included below:

Using the adjusted cost basis allows you to calculate the adjusted gain or loss, which is almost always lower than the 1099-B’s gain or loss.

Well, that sums up all the neat ways that Uncle Sam can unintentionally gouge you, including preventing Roth IRA contributions, disadvantaging ESPPs, and double taxing RSUs. I hope your able to save a few dollars as a result, if not this tax year, at least in the years to come.

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

comments powered by Disqus