Information Theory in IoT (Part 1)

This is the first part in a two part series and will focus on the broad concepts of information theory. Part two will discuss converting natural data into independent identically distributed values as well as Huffman encoding.

Pictured is Claude Shannon, the founder of Information Theory. I’ve recently been reading Information Theory: A Tutorial Introduction by James Stone, partly out of curiosity, partly out of the hope that what I learn may be in some way applicable to my current work. Sure enough, the opportunity to apply what I’ve learned very quickly presented itself.

At Nautilus our hardware stores past workouts until they can be transferred to the cloud by a connected mobile device. Unfortunately like all computers, the machine’s Universal Control Board (UCB) has limited memory space. As new functionality is added to the hardware, less space remains for offline workout storage. This presents an opportunity for the application of information theory.

Before we go any further I’d like to define some terms. In information theory the concept of “entropy” represents uncertainty. “Information” is the resolution of that entropy. Information is transmitted through a channel as a “signal”. A channel can consist of a number of transmission mediums, from radio waves, to sound waves, to fiber-optic cables. Regardless of the medium however there will always be some degree of “noise” (hence the common-enough phrase “noise-to-signal ratio”). Noise is garbage data that is injected into the channel through various phenomena.

At Nautilus it’s not uncommon to have electromagnetic noise, especially from treadmill motors. That’s because those motors use and radiate a lot of electromagnetic energy while under the load of propelling a user backward so that they don’t run off the front of the machine. Our treadmills, just like the rest of our connected exercise equipment, are considered “Internet of Things” (IoT) devices because they connect to the internet (albeit indirectly through a user’s phone). They do this in order to persist a user’s workouts in the user’s digital exercise journal.

Because these devices are recording natural phenomena, a lot of the data is interrelated. A user’s belt speed does not jump from 5mph to 10mph. Instead it gradually increases from 5.0, to 5.1, to 5.2 and so on. Because of this the data is said to be “related”, that is, each successive piece of data resolves less entropy (and thus provides less information) than the last. A classic example of this is the gameshow “Wheel of Fortune”. Because the arrangement of letters in words in the English language is not random, contestants are able to solve the word puzzles by inferring unknown letters through the placement of their known neighbors. The inverse of this rule is a cornerstone of information theory: optimally compressed information is indistinguishable from “noise” because all the redundancies in the data have been removed. Without the encoder/decoder algorithm there is no way that you can interpret the data, whereas with related data some kind of translation may eventually be possible. This seemingly random arrangement of information is what is known as “IID”, or Independent, Identically Distributed data. Which brings us back to the original topic, the storage of as many offline workouts as possible.

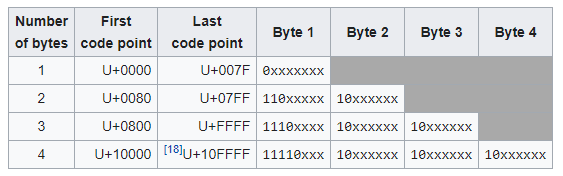

Currently we use C programming language data types combined with UTF8 encoding for our data. UTF8 is designed to encode messages into 1-4 byte long code-words, depending on the number of significant bits in the numerical value of the value. The following table shows the structure of the encoding. The x characters are replaced by the bits of the code point.

Because of its flexibility, UTF8 has become the default encoding for most text-based encoding. But as we’ll see in the second part of the series, a much more efficient encoding is possible if the encoding is specifically created for our particular problem space.

Image of Claude Shannon obtained with permission from https://opc.mfo.de/detail?photo_id=3807

comments powered by Disqus