The Squash Merge

I recently took up a contract job where the developers use the squash merge option in GitHub. According to GitHub’s documentation “When you select the Squash and merge option on a pull request on GitHub.com, the pull request’s commits are squashed into a single commit. Instead of seeing all of a contributor’s individual commits from a topic branch, the commits are combined into one commit and merged into the default branch.” When I asked the developers why they chose this option, the explanations were pretty typical:

“It makes the git history easier to read at a glance.”

“I don’t always have a meaningful commit message for in-progress features.”

“Each commit should stand on its own as a functional product.”

“Each commit should be annotated with the name of the feature branch that it was a part of.”

These on the surface seem like reasonable statements. But I’m not a fan of squash merges, and as I’ve continued to work with them my dislike has only grown. My complaints are legion, but for the sake of brevity I’ll outline my two biggest gripes.

Squash merges erase history. When trying to determine how a bug was introduced or why a change was made for a particular line of code, I’ll often look at just the history for that particular code snippet. I sometimes refer to this as “git archeology”. Unfortunately with a squash merge the granularity of history for that line of code is completely lost. It would be like an actual archeologist trying to determine whether an artifact belonged to the paleolithic, bronze, or iron age without the benefit of Stratigraphy. They could make some educated guesses (is the object made out of bronze? Yes? Then maybe it’s from the bronze age?), but would never be sure. This is because, as historians well know (thanks in part to stratigraphy) bronze objects continued to be made well into the iron age.

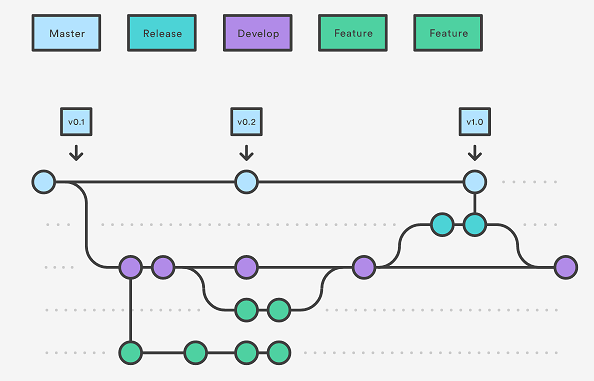

My second major complaint against squash merges is that it exacerbates the complications that occur with pull requests (PRs) between long lived branches. This actually happened at my contract job and the other developers had no idea why they had as many merge conflicts as they did. I had to patiently explain to them that every time that they merged the first branch into the second, all the code changes were being consolidated into a single commit on the target branch after the merge by GitHub, but NOT on the source branch. This creates two separate authors for the exact same code changes. The target branch is left with GitHub as the author of the (now squashed) code. The source branch however keeps its original authors. This is very confusing for the automated difference checks that are executed as part of the git version control system. After executing a squash merge between two branches, the next time a pull request is opened between those two branches, git needs to determine what changed. However, it has no idea how to pick between two different commit authors, even when the lines of code that they authored are identical. So a human developer needs to painstakingly go line by line and tell git which author it should prefer when deciding which version of “history” (either the target or source branch’s) should be preserved. The deepest irony, of course, is that none of these painstakingly made decisions will ultimately matter, because after the PR is merged GitHub will just re-write history with it’s own squashed version, triggering the process all over again in the next PR.

I don’t want to leave the reasons for squash merges unaddressed though, so I’ll address them next. For the argument “It makes the git history easier to read at a glance”, I’d really like to know why you need to look at it in a glance. If you want to tell what features a particular release branch has you can filter the logs to merge commits, which will list all the merged features and bugfixes. In answer to: “I don’t always have a meaningful commit message for in-progress features.” and “Each commit should stand on its own as a functional product,” I am strongly tempted to wryly to state “that sounds like a you problem.” For the sake providing actionable means of improvement I’ll shamelessly quote from the Such Dev Blog concerning the practice of atomic commits:

atomic git commits means your commits are of the smallest possible size. Each commit does one, and only one simple thing, that can be summed up in a simple sentence. The amount of code change doesn’t matter. It can be a letter or it can be a hundred thousand lines, but you should be able to describe the change with one simple short sentence.

For the final argument “Each commit should be annotated with the name of the feature branch that it was a part of.”, I have a rather simple solution, a bash alias that allows me to prepend each commit message I write with the Jira ticket number before committing it locally and pushing to remote. The script is below:

# gcamp: Git commit all with a message prepended by the current branch prefix and then push

gcamp() {

branch=$(git rev-parse --abbrev-ref HEAD)

split "$branch" / parts

prefix=${parts[1]} # bash arrays are 1-indexed

# echo "$prefix $@"

git commit -a -m "$prefix $@"

git push -u origin HEAD

}

# split: splits a string in bash into an array

split() { # args: string delimiter result_var

if

[ -n "$ZSH_VERSION" ] &&

autoload is-at-least &&

is-at-least 5.0.8 # for ps:$var:

then

eval $3'=("${(@ps:$2:)1}")'

elif

[ "$BASH_VERSINFO" -gt 4 ] || {

[ "$BASH_VERSINFO" -eq 4 ] && [ "${BASH_VERSINFO[1]}" -ge 4 ]

# 4.4+ required for "local -"

}

then

local - IFS="$2"

set -o noglob

eval "$3"'=( $1"" )'

else

echo >&2 "Your shell is not supported"

exit 1

fi

}

That about sums up my arguments against the commit squash and my rebuttals against some of the arguments for the squash merge by its advocates. My hope is that some of you will be able to use this post as ammunition when advocating for just using the default GitHub merge mechanism with your teams. Until next time!

comments powered by Disqus